An LLM re-write of Seven Pillars of Wisdom

Introduction

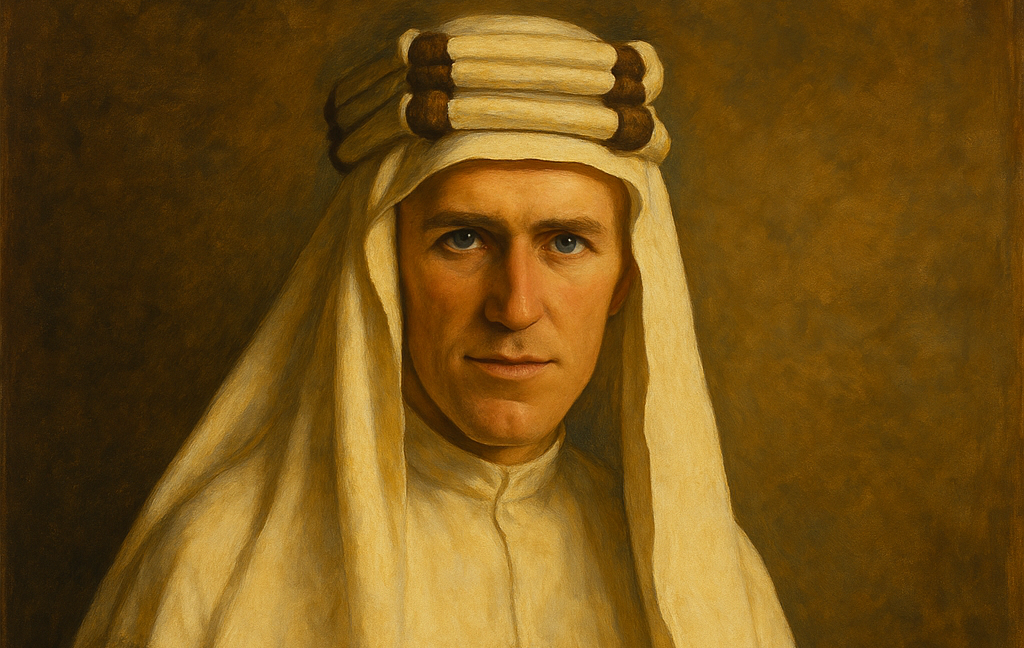

I was looking for something to read in June, and decided to read Seven Pillars of Wisdom by T.E. Lawrence, the author’s account of his leading the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire in World War I. The book was made into a movie, Lawrence of Arabia. As the author died in 1935, the book is long out of copyright, and I downloaded a free copy from Standard Ebooks.

I thought I would love this book - it’s a first hand account of significant historical events, in a different time and place, and full of action. But I didn’t care for T.E. Lawrence’s writing style (though I understand some praise it). I put it down at chapter 10, and moved on to another book.

And then I thought, Large Language Models (LLMs) are great at style transfer. What if I took the content of the book, and had an LLM re-write it in a different style?

Experimentation

Variations to Explore

There were a few things I wanted to try:

- I wanted to try a couple models. Reviewing OpenAI’s and Anthropic’s documentation, I settled on trying OpenAI’s GPT-4 and Anthropic’s Sonnet.

- Rather than define a style, I thought it might make sense to write in another author’s style. Just randomly, Nick Hornby (Fever Pitch, High Fidelity, About A Boy) popped into my head, and I thought, he’s British and his writing is pretty accessible. And then I also tried Erik Larson - an American author known for his historical non-fiction writing.

- I didn’t want to mess around with formatting. I started with the Standard Ebooks epub, which split the content across 8 files. I opened each file, and converted the book in chunks, with the same prompt, between chapter and other headings, and replaced the content one chunk at a time. I created a quick script, parseepub.py, to automate the process.

Original Passage

I chose the following random passage from the book to compare prompts and models:

But before this we had had hopes of Mesopotamia. The beginning of the Arab Independence Movement had been there, under the vigorous but unscrupulous impulse of Seyid Taleb, and later of Yasin el Hashimi and the military league. Aziz el Masri, Enver’s rival, who was living, much indebted to us, in Egypt, was an idol of the Arab officers. He was approached by Lord Kitchener in the first days of the war, with the hope of winning the Turkish Mesopotamian forces to our side. Unfortunately Britain was bursting then with confidence in an easy and early victory: the smashing of Turkey was called a promenade. So the Indian Government was adverse to any pledges to the Arab nationalists which might limit their ambitions to make the intended Mesopotamian colony play the self-sacrificing role of a Burma for the general good. It broke off negotiations, rejected Aziz, and interned Sayid Taleb, who had placed himself in our hands.

By brute force it marched then into Basra. The enemy troops in Irak were nearly all Arabs in the unenviable predicament of having to fight on behalf of their secular oppressors against a people long envisaged as liberators, but who obstinately refused to play the part. As may be imagined, they fought very badly. Our forces won battle after battle till we came to think an Indian army better than a Turkish army. There followed our rash advance to Ctesiphon, where we met native Turkish troops whose full heart was in the game, and were abruptly checked. We fell back, dazed; and the long misery of Kut began.

Meanwhile, our Government had repented, and, for reasons not unconnected with the fall of Erzerum, sent me to Mesopotamia to see what could be done by indirect means to relieve the beleaguered garrison. The local British had the strongest objection to my coming; and two Generals of them were good enough to explain to me that my mission (which they did not really know) was dishonourable to a soldier (which I was not). As a matter of fact it was too late for action, with Kut just dying; and in consequence I did nothing of what it was in my mind and power to do.

OpenAI - GPT4 Re-write in the style of Nick Hornby

My prompt was: “Re-write the following passage in the style of Nick Hornby:”. Here’s what I got from GPT-4:

Before all this, there were glimmers of hope for Mesopotamia. The Arab Independence Movement had its roots there, driven by the dynamic but morally dubious Seyid Taleb, and then later by Yasin el Hashimi and the military league. Aziz el Masri, Enver’s nemesis who was living in Egypt, largely indebted to us, was idolised by Arab officers. In the early days of the war, Lord Kitchener had approached him, hoping to bring the Turkish Mesopotamian forces over to our side. But, Britain was then overly optimistic, expecting swift and easy victory: the defeat of Turkey was casually referred to as a walk in the park. So, the Indian Government wasn’t keen on making promises to the Arab nationalists that could clip their wings, limiting their dreams of making the proposed Mesopotamian colony a selfless Burma for the common good. They called off negotiations, dismissed Aziz, and confined Sayid Taleb, who had willingly put himself at our mercy.

In came our troops, bulldozing their way into Basra. The opposing soldiers in Irak were mostly Arabs caught in the unenviable predicament of having to fight for their long-standing oppressors against a people they had long visualised as liberators, who stubbornly refused to play the part. Unsurprisingly, their will to fight was weak. Our forces triumphed in battle after battle, leading us to believe that an Indian army was superior to a Turkish one. Then came our reckless advance to Ctesiphon, where we encountered native Turkish troops fully committed to their cause, and were abruptly halted. We retreated, disoriented, and the long drawn-out ordeal of Kut began.

In the meantime, our Government had a change of heart, and, for reasons not unrelated to the fall of Erzerum, sent me to Mesopotamia to explore indirect means of relieving the besieged garrison. The local British were strongly opposed to my arrival; and two of their Generals were gracious enough to tell me that my mission (which they didn’t really understand) was beneath a soldier (which I wasn’t). In reality, it was too late for action, with Kut on its last legs; and as a result, I didn’t do anything that I had intended and was capable of doing.

I then asked: “Historical content aside, does it match Nick Hornby’s style?”

While the text includes an engaging narrative, it doesn’t truly reflect Nick Hornby’s signature style. Hornby’s work tends to use a very conversational tone, uses humor as a tool to delve into serious topics, often has numerous pop culture references, and is known for creating characters that readers can relate to. The use of first-person perspective is consistent with Hornby’s style, but the tone of the piece is more serious, historical, and formal than Hornby’s typical writing. The narrative also lacks usual humorous undertones and contemporary references. So, while it’s well-crafted, it doesn’t uniquely reflect Hornby’s distinctive voice.

Claude Sonnet 3.7 Re-write in the style of Nick Hornby

And from Claude Sonnet 3.7:

So we had high hopes for Mesopotamia. I mean, not the kind of hopes you have for your football team winning the cup or finding that rare vinyl you’ve been hunting for years, but proper political hopes. The Arab Independence Movement had kicked off there - think of it as the Sex Pistols of Middle Eastern nationalism, all energy and attitude but with questionable management.

There was this bloke, Seyid Taleb, bit of a wheeler-dealer type, like that mate who’s always got a scheme on the go that sounds brilliant after four pints. Then Yasin and his military league mates joined the band. And Aziz el Masri - he was the Arab officers’ Kurt Cobain, the guy they all wanted to be.

Lord Kitchener - picture a Victorian headmaster with a moustache you could sweep the floor with - approached Aziz right at the start of the war. The plan was to get the Turkish forces in Mesopotamia to switch sides, like when a midfielder transfers mid-season to your biggest rivals. But Britain was absolutely buzzing with overconfidence then, thinking they’d wrap up this war business in time for tea. Beating Turkey was supposed to be a walk in the park - the equivalent of your pub team playing against a bunch of hungover wedding guests.

The Indian Government, being total corporate suits about the whole thing, didn’t want to make any promises to the Arab nationalists. They had this master plan to turn Mesopotamia into another Burma - not the nice place you might go backpacking, but the exploited colony kind. So they ghosted Aziz and locked up Sayid Taleb, who’d foolishly put himself in our hands, like lending your favorite album to someone who’s just bought a Nickelback CD.

Then we just barged into Basra like drunk blokes pushing their way to the bar. The enemy troops were mostly Arabs stuck in this completely shit situation - having to fight for the people who’d been oppressing them against the people who were supposed to be their liberators but who were acting like total prats. Unsurprisingly, they fought with all the enthusiasm of a teenager asked to tidy their room. We won loads of battles, which gave us this completely wrong idea that our Indian army was better than the Turkish army - classic case of mistaking luck for skill, like thinking you’re a pool shark because you beat your dad once.

Then came our stupid advance to Ctesiphon, where we met actual Turkish troops who were properly into it. They stopped us dead, like when you’re chatting up someone way out of your league and they finally say, “Actually, I’m just waiting for my boyfriend.” We stumbled back, completely shell-shocked, and then the whole miserable Kut siege began - the military equivalent of being stuck in the world’s worst bed and breakfast with no return ticket.

Meanwhile, our Government had a change of heart - funny how losing battles does that - and sent me to Mesopotamia to see if I could help the trapped garrison through some backdoor methods. The local British officers were about as happy to see me as a vegan at a barbecue competition. Two Generals actually took time out of their busy schedule to tell me my mission (which they knew sod all about) was dishonourable for a soldier (which was ironic since I wasn’t one). But it was too late anyway - Kut was on its last legs, like a pub at 3am with the lights coming on. So I did precisely nothing of what I could have done, which, looking back, feels a bit like owning the perfect comeback but only thinking of it on the bus home.

Again, I prompted ChatGPT, does this match Nick Hornby’s style?

Yes, this text does match Nick Hornby’s writing style. The narrative style is conversational and captures the British vernacular effectively. The humor is evident and there is a frequent use of pop culture references and similes drawn from everyday experiences. The text weaves in serious historical events with a humorous take and creates characters that are relatable and vivid. This mirrors Hornby’s noted ability to incorporate humor into serious topics, making complex issues more accessible and palatable for readers. The intimate, confessional tone that is a hallmark of Hornby’s style is also prominent in this text.

I thought I saw patterns in the text that I didn’t recognize from Nick Hornby’s books - “It’s like” appears 90 times through the text. But then I checked About A Boy (appears once), A Long Way Down (appears 8 times), and High Fidelity (appears 11 times) - given the length of Seven Pillars - 90 times isn’t crazy.

Claude Sonnet 3.7 Re-write in the style of Erik Larson

A few things I noticed in this version:

- It’s LONG

- The LLM is inserting dates and other details that aren’t in the original text. It’s not clear if this is being pulled from other sources in its training, or if it just being made up.

- When I first considered Erik Larson, I was thinking “what history books have I enjoyed?”. And it wasn’t until I read this adaptation that it occurred to me that Seven Pillars wasn’t written as a history book - it’s a first person account of an experience. And this re-write is all 3rd person. It made me re-think which author’s style might work best.

On the morning of January 3, 1916, as winter fog rolled across the Tigris River, the siege of Kut al-Amara entered its thirty-ninth day. Major General Charles Townshend’s trapped British-Indian garrison was already rationing food to quarter portions. No one yet knew that this would become one of the most humiliating defeats in British military history. But the seeds of this disaster had been planted long before, in the heady optimism of a war that many believed would be over by Christmas.

Mesopotamia had once held such promise. In the years before the Great War, the ancient land between the Tigris and Euphrates had become the cradle not just of civilization but of a new Arab awakening. In the narrow streets of Baghdad and the bustling port of Basra, men gathered in coffee houses thick with hookah smoke to whisper of independence. Chief among these dreamers was Seyid Taleb, a man whose piercing eyes and carefully trimmed beard belied his ruthless political instincts. British intelligence officers described him as “vigorous but unscrupulous,” a characterization that did nothing to diminish his appeal among the nascent Arab nationalists.

By 1914, the movement had grown to include Yasin el Hashimi, a former Ottoman officer whose military bearing and tactical mind attracted young Arab soldiers to his cause. While Seyid worked the political angles, Yasin built a network within the Ottoman military ranks—a secret society of Arab officers awaiting their moment.

Meanwhile, in Cairo, another figure loomed large in this unfolding drama. Aziz el Masri, once a rising star in the Ottoman military and bitter rival to Enver Pasha, now lived in exile under British protection. Aziz’s name was spoken with reverence among Arab officers throughout the Ottoman ranks. He had become something of a folk hero—a symbol of Arab dignity in an empire increasingly dominated by Turkish nationalists.

When war erupted in August 1914, Lord Kitchener, whose imposing mustache and stern visage stared from recruitment posters across Britain, saw an opportunity. As the newly appointed Secretary of State for War, Kitchener understood the strategic importance of Mesopotamia better than most. On August 29, as German armies pushed through Belgium and France, Kitchener dispatched an envoy to meet with Aziz in a secluded garden behind Cairo’s Shepheard’s Hotel. The proposition was audacious: help turn the Ottoman Arab regiments in Mesopotamia to Britain’s side.

But in London and Delhi, an intoxicating overconfidence pervaded the corridors of power. “The war will be over by Christmas,” officials confidently told one another over brandy and cigars. Turkey was dismissed as “the sick man of Europe,” its defeat considered inevitable. “A mere promenade,” one Colonial Office memorandum termed the anticipated campaign. This fatal hubris infected policy.

The Viceroy’s Council in India, which administered Britain’s jewel in the crown, had its own designs on Mesopotamia. They envisioned not a free Arab state but another colonial possession—one that would serve as a buffer for India and a source of oil for the Empire. Any promises to Arab nationalists would only complicate these ambitions. The council wanted Mesopotamia to serve the Empire as Burma did: a resource-rich territory that existed primarily for the benefit of British imperial interests.

On October 31, 1914, as the first autumn leaves fell in London, the Indian Government abruptly terminated negotiations with Aziz. That same week, they detained Seyid Taleb, who had unwisely placed himself in British hands. The man who might have led an Arab uprising now found himself imprisoned on a British warship anchored in the Persian Gulf, watching through a porthole as his dreams of independence drifted away like smoke.

Instead of diplomacy, Britain chose force. On November 6, 1914, as a light rain fell on the Persian Gulf, British Indian troops splashed ashore at Fao, beginning their march toward Basra. The Ottoman forces they faced were predominantly Arab conscripts caught in a cruel dilemma—forced to fight for Turkish officers who treated them with contempt, against a British force widely rumored to be coming as liberators. But these same British “liberators” had just imprisoned their most prominent leader and rejected their aspirations for independence.

A Turkish officer later captured at Basra told his British interrogator, “You cannot imagine what it is to command men who secretly hope for your defeat.” The Arab soldiers fought accordingly, often surrendering at the first opportunity or melting away into the marshlands that flanked the rivers.

Victory followed victory for the British forces. In the officers’ mess tents, as they dined on tinned beef and warm beer, a dangerous notion took hold: that the Indian Army was superior to Turkish forces. This misconception would cost thousands of lives.

On November 22, 1915, under a sky the color of burnished steel, British forces advanced toward Ctesiphon, the ancient Parthian capital. Here, they encountered not reluctant Arab conscripts but hardened Turkish divisions from Anatolia—men fighting for their homeland with religious fervor. The battle that followed shattered British illusions. Artillery fire tore through advancing columns. Machine guns chattered death from concealed positions. By nightfall, the British force was in retreat, leaving behind hundreds of dead and wounded.

They fell back to Kut al-Amara, a small town encircled by a loop of the Tigris River. What was intended as a temporary defensive position became a trap. The Turkish forces, sensing vulnerability, surrounded the town. The siege had begun.

By early 1916, as Townshend’s men began slaughtering cavalry horses for meat, the British Government recognized its catastrophic miscalculation. It was in this atmosphere of desperation that they turned to unconventional measures. On a cold February morning, a telegram arrived authorizing my mission to Mesopotamia—an attempt to use “indirect means” to relieve the garrison.

The reception that awaited me in Basra was frigid in a way the desert climate could never match. Two British generals, their faces flushed with indignation beneath their pith helmets, summoned me to headquarters. In a room where ceiling fans stirred the hot air without cooling it, they lectured me on honor and propriety. My mission, which they knew only by rumor, was “dishonorable to a soldier,” they insisted. I did not bother to point out that I was not, in fact, a soldier.

What neither of us knew then was that it was already too late. Kut was beyond salvation. On April 29, 1916, after 147 days of siege, Townshend surrendered his entire force of 13,000 men. More than half would not survive the brutal captivity that followed. Another British dream had died in the ancient land between the rivers—a victim of imperial hubris and the complex realities of a region that has never yielded easily to foreign designs.

Claude Sonnet 3.7 Re-write in the style of Helen Russell

After recognizing the challenges of the re-writing in Larson’s style, I wanted to look for an author who was English, and wrote in the first person about their personal experience. I decided to try Helen Russell, known for her writing about her experience of living in Denmark:

We’d pinned our hopes on Mesopotamia, you see. That’s where the Arab Independence Movement had first taken root – a plucky little uprising spearheaded by the dynamic (if somewhat morally flexible) Seyid Taleb, before Yasin el Hashimi and his military chums took up the baton.

Aziz el Masri was rather the poster boy for Arab officers at the time – Enver’s rival and thoroughly in our debt while lounging about in Egypt. Lord Kitchener approached him as war broke out, hoping to woo the Turkish Mesopotamian forces to our side. But here’s the thing: Britain was absolutely bursting with misplaced confidence then – positively giddy with it! The whole Turkish situation was dismissed as a “promenade” – a walk in the park, if you will.

The Indian Government, in their infinite wisdom, decided against making any promises to Arab nationalists that might interfere with their grand colonial designs. They wanted Mesopotamia to be the next Burma – a selfless little territory working for the greater good. So they abruptly ended talks, gave Aziz the cold shoulder, and locked up Sayid Taleb who had rather naively placed himself in our hands.

They then marched into Basra with all the subtlety of a rhinoceros at a garden party. The enemy troops in Irak found themselves in the most awkward of positions – Arabs forced to fight for their oppressors against what should have been their liberators, had we not been so stubbornly opposed to playing that part. Unsurprisingly, their fighting spirit was somewhat lacking. Our forces triumphed repeatedly until we developed the entirely mistaken notion that an Indian army was superior to a Turkish one. Hubris, thy name is Empire!

This led to our terribly ill-advised advance to Ctesiphon, where we encountered actual Turkish troops with their hearts fully committed to the cause. We were promptly and thoroughly walloped. We retreated, utterly bewildered, and thus began the protracted misery of Kut.

Meanwhile, our Government had experienced something of a change of heart (not entirely unrelated to Erzerum’s fall) and dispatched yours truly to Mesopotamia to see what might be done through back channels to rescue the besieged garrison. The local British were about as pleased to see me as one would be to discover mold in the butter dish. Two Generals took it upon themselves to explain that my mission (which they didn’t actually understand) was beneath the dignity of a soldier (which I wasn’t). The timing was dreadful anyway – Kut was already at death’s door – so I accomplished precisely none of what I had both the intention and capacity to do.

Honestly, the whole affair was managed with all the grace and foresight of a toddler attempting brain surgery.

I didn’t care for this version - perhaps in part due to the fact that I’m not familiar with Helen Russell’s work.

A fun idea

The re-write by Claude Sonnet, in the style of Nick Hornby, was my favourite - I loved the humour, and the pop culture references reflect my cultural experience. One line I have to share, from a different passage in the book, that I particularly loved from this iteration:

I was trying to be Lawrence of Arabia, but most of the time I felt more like David Brent of Arabia - completely out of my depth and probably doing more harm than good.

I decided to proceed with this variation for my re-write, and called it Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Pop Culture-Laden Large Language Model Reworking.

This was a fun idea, but in the end:

- I don’t think I achieved my goal of making the book more interesting for me. I stopped reading the Pop Culture-Laden adaptation around the same place I stopped reading the original book.

- As a casual reader, with limited familiarity of the analysis of writing styles, it’s hard to tell if the re-write is actually in the style of the target author. Looking at the GPT-4 adaptation above - does it read like Nick Hornby? Can’t tell.

- It was interesting to see the Erik Larson variation pick up details and shift to third person - I hadn’t even considered these as style elements, when they are. This could likely be addressed by providing more specific instructions in the LLM prompt.

- Even when instructed to just do a style transfer, the LLM was adding dates and details not in the original text. Following any LLM manipulation, any non-fiction work would require serious review ensure that the integrity of the original content is maintained. Imagine a sequence of events being changed by the LLM, such as “Who shot first?”. In the case of fiction, this feels like it would be less important - lots of stories are retold, and tweaked for new audiences.

Download the eBook: Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Pop Culture-Laden LLM Reworking

Interested in checking the out the re-write for yourself? (note: I didn’t finish reading it myself, I share it for the curious!)

You can download my favourite variation of my LLM re-writes, the Nick Hornby style re-write executed by Claude Sonnet: Seven Pillars of Wisdom: A Pop Culture-Laden Large Language Model Reworking.