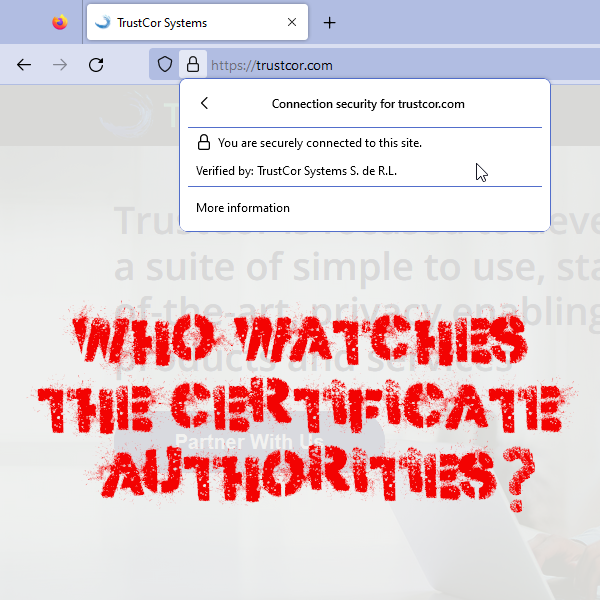

Who watches the certificate authorities?

In November, I was following a news story the Washington Post broke about Trustcor, a Certificate Authority with root certificates pre-loaded in all popular browsers. A few academics identified some problematic relationships and facts about Trustcor that puts into question the process used by Chrome, Firefox, and Safari to determine which companies can issue the certificates that our browsers use to indicate a connection is secure. From the article:

The website site lists a contact phone number in Panama, which has been disconnected, and one in Toronto, where a message had not been returned after more than a week. The email contact form on the site doesn’t work. The physical address in Toronto given in its auditor’s report, 371 Front St. West, houses a UPS Store mail drop.

Would this company pass your audit? I was familiar with the role played by root certificates in browsers, and understood there was an assessment process for inclusion completed by the teams that build browsers. I get that a process can’t catch everything, but I was surprised about how flagrant this evidence of untrustworthy behaviour was.

I was pleased to see in the Post’s follow up story that Mozilla and Microsoft are removing Trustcor’s root cert from their browsers. This follow-up article also presents the possibility that the root cert was leveraged by Packet Forensics for man-in-the-middle interception of encrypted traffic:

Packet Forensics first drew attention from privacy advocates a dozen years ago.

In 2010, researcher Chris Soghoian attended an invitation-only industry conference nicknamed the Wiretapper’s Ball and obtained a Packet Forensics brochure aimed at law enforcement and intelligence agency customers.

The brochure was for a piece of hardware to help buyers read web traffic that parties thought was secure. But it wasn’t.

“IP communication dictates the need to examine encrypted traffic at will,” the brochure read, according to a report in Wired. “Your investigative staff will collect its best evidence while users are lulled into a false sense of security afforded by web, email or VOIP encryption,” the brochure added.

Researchers thought at the time that the most likely way the box was being used was with a certificate issued by an authority for money or under a court order that would guarantee the authenticity of an impostor communications site.

They did not conclude that an entire certificate authority itself might be compromised.

Can you imagine the potential for man-in-the-middle abuse by ISPs and VPN service providers if they had root certificates in our browsers (examples of untrustworthy behaviour by VPN providers)? Given the challenges with this model, it’s interesting we haven’t seen more evidence of widespread abuse:

-

Was this situation isolated and unique?

-

Why doesn’t every malicious actor get a root certificate?

-

Are there limited incentives to intercepting traffic?

-

Perhaps regular law/ethics are sufficient to deter intercepting traffic?

-

Is this happening everywhere all the time, and there’s limited impact?

-

Perhaps most traffic isn’t of value, so traffic interception is limited and targeted?

I recommend reading Delegating trust is really, really, really hard, a reflection on the matter by Cory Doctorow. Hopefully, the Trustcor story brings greater attention to the issue, and more attention will be paid by development teams & users to the root certificates pre-loaded in their browsers.